Behavioral Ultrasound- child dental x ray

child

dental x ray On or around April

1, 1980, someone decided the objective of an ultrasound exam was a set of

images. It seems plausible on the surface. It fits the job description of

ultrasound technologists, and it mirrors the role of manufacturers. From the

standpoint of medical diagnosis, though, that notion departs from medical

teachings going back to Hippocrates, probably even earlier to the Ebers

Papyrus. I am sure the originator could

not have been a radiology. I hope

that behavioral psychology might provide

us with an insight.

In the Beginning

The early B-Mode

ultrasound settlement included physicians with a wide array of specialty

backgrounds. After some initial, and very significant, technical advances, a

lot of the daily clinical work across the country was handled by

radiologists. Along the way, cardiologists

moved up to high-speed imaging from TM tracings and obstetricians began to

offer ultrasound to their own patients. Now, we have separate ultrasonic

fiefdoms in multiple areas – the ER, the ICU, MSK, family, medicine, and, at

the recent AIUM, there were multiple presentations and courses on dermatologic

applications.

The early days were

a simple time. There wasn’t much known,

you didn’t have to know much, and clinical expectations were low. Acquiring

satisfactory images took a long time, and they had a low yield of actionable information.

The only impetus for clinical usage seemed to be avoiding ionizing radiation

exposure. Most of the uses revolved around distinguishing “cysts” from “solids”

for finding fluid collections of one type or another, or for looking at

movements of structures in a fluid field.

I think of the

decade from 1975 as the golden (and radiologic) Age of Ultrasound. There was a

vast amount of academic research of imaging fundamentals leading to some major

improvements in instrumentation, and there was a gigantic deepening of clinical

sophistication with a rich peer-reviewed literature. There were some massive technical downsides.

Image noise content was so high and data acquisition so varied from

place-to-place, from operator-to-operator, and between multiple types of

instruments that there was never any effective way to establish practice

standards, make education uniform, or extract quantitative descriptors of

tissue properties.

Nevertheless, the

clinical results of the early experience with mechanical and electronic

scanners were very good, and the field flourished over a wide span of

diagnostic applications. An essential factor may have been due to the way

radiologists handle visual data. The starting points for all imaging modalities

are knowing where to look and how to look. The real work is in fitting

information from images with everything you know clinically about the patient

and everything you should know about what can go wrong with that patient’s population cohort. The “list” of possibilities is prioritized by

the potential lethality or severity of probable conditions. The radiologist has

to have an understanding of the utility of every other diagnostic procedure in

his or her own facility in order to select the safest and most informative way

of resolving a clinical question as a procedural sequence.

Another covert facet

of image interpretation is the ability to extrapolate the consequences of a

diagnosis. This might seem obvious in a fetal or pediatric ultrasound study,

but it is always a factor. Perhaps this is why radiologists have been so

obsessed with the pick-up rates, the sensitivity, and the specificity of

screening exams ever since the days of mobile vans for tuberculosis detection.

If you miss a tiny, eminently miss-able, lesion, the patient might lose years

of life. Over-diagnosis has its own set of painful and costly detriments.

Fast and/or Slow

My limited exposure

to “dual process theory” is from Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

(Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 2011 ISBN: 978-0374275631). This book has been

referred to as a masterpiece. It has won every possible award. It explored the

life work of the author and his late collaborator Amos Tversky, and it centers

on “prospect theory” – the basis for Professor Kahneman’s Nobel Prize in

Economics. The subject is treated scientifically. It describes many ingenious

experiments, which established there are two main ways people respond to

situations, referred to as “fast” and “slow.” The works of other researchers is

detailed selflessly, and there are no wild speculations. Since this work

concerns basic human behavior, it would seem logical that it applies to

ultrasound, too.

Fast and slow are

metaphors. The fast system is instant, automatic, unconscious, capricious,

effortless, and always on. It is triggered by unconscious perceptions and works

by ingrained associations and patterns that are very hard to change. It is

incapable of calculation. It is not influenced by statistics or objective

reality. It is gullible and can be misled. Effective ads appeal to the fast

system.

Slow is rational,

conscious, suspicious, and very effortful, because it involves a lot of energy

expenditure. Fast can be brilliant, but prone to systemic errors; slow can be

thorough and plodding, but it is not “perfect” either. Slow is mostly off, and

it can be derailed by emotionally-tainted fast perceptions, as well as a

limited knowledge base.

I’ve always believed

in love at first sight. That is an ultimate fast system response. Fast is very

efficient, and it works by a system of heuristics. “Heuristics” is a relatively new word, coined

from a Greek root related to discovery, so its definition remains somewhat

pliable. I encountered the term in college (it’s probably common in grade

schools now) in issues related to computer searching, pattern recognition, and

artificial intelligence. An heuristic is a fast, efficient, down-and-dirty

shortcut for getting a workable and/or reasonable, approximate solution to a

complex, sometimes analytically insoluble, problem. In Thinking, Professor

Kahneman identifies several classes of heuristic that the fast system relies

upon. One is the “halo effect” in which your impression becomes generalized

over the object, i.e. love at first sight = everything about the object of your

affections is lovable and perfect. Heuristics are mental habits. It is also via

heuristics that biases emerge as influencers.

A Detour to

Psychiatry and Genetics

Fast has been

proposed as the evolutionary default state. Each of us has a balance point

between fast and slow in our lives and work that I want to explore a little

more. People who are locked into either of these operational states exclusively

have well defined forms of psychopathology. People with very different balances

between fast and slow cannot communicate very well. People who are mainly fast

double down on their opinions, even when they have no factual substance or

foundation, and mainly slow people cannot understand the emotional fervor of

preferential fasts. All of my patients are referred, and to tell you the truth,

I have always found a lot of remote referral patterns to be somewhere between

rigid and irrational. I would guess these referrals are fast responses by

practitioners who don’t know a lot about ultrasound, don’t keep up with

technical advances in the field, and often resist informed suggestions about

effective utilization of resources.

Let’s start with the

common expression “Crazy runs in families.” This is true, but it has been very

difficult to clarify because a family tree peppered with psychoses has so much

variability by type, severity, and age of onset that their occurrence can seem

random or at least unrelated. Genome

sequencing has identified multiple loci for a spectrum of psychoses in which

the specific whose combination of genes, and their penetrance seem to explain

those variations. At one end of the

spectrum is potential brilliance, the other hallucinatory divorce from reality.

Think of the phrase: “She’s as pigheaded as her father.” Doesn’t it seem likely

that the balance between fast and slow is also coded into our genomes?

Postgraduate Medical

Education

How has medicine

coped traditionally with these unrecognized fast/slow issues? Take a bunch of

young people with good hearts and stellar academic records. They have

altruistic heuristics, learn well, and adapt to variability and chaos. This is

an ideal, new medical school class. They receive a progressive increase in information

over several years to nourish their slow systems. But, there is even more

emphasis on interactive topics, like taking a history. This can be viewed as a

way to mold the fast system for dealing, bonding, and gaining the trust of new

patients despite first impressions on both sides. It also creates an indelible

bond with our professional ancestors who have all had to cope with the same

issue.

Medical specialty

training expands upon integrating the two systems in some way. I look back in

awe, admiration, and fondness to my time as a diagnostic radiology house

officer at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). I was probably not so

sanguine at the time. I presume the educational goals of all diagnostic

radiology training programs are identical everywhere. I have never had any need

to inquire of colleagues about their own background, because of the

similarities of our perceptions and work habits.

Reading plane films

started out as a slow system endeavor. You try to look at every detail of all

of the views you have before you. It’s very tiring, exhausting, actually, and

that’s before you even start to integrate clinical information and narrow down

diagnostic possibilities. You keep hearing phrases like, “get the Gestalt”

without knowing what that means until, magically, you get it. There are

withering comments for errors, in public at conferences and more privately when

reviewing a board full of cases. There is scarcely anything positive for a good

call. It is much milder than the surgical experience. The system is geared

toward emergent decision making and directed towards avoiding errors, and if an

error is made, to be sure that it is not repeated.

The only way to

handle a large volume of imaging studies efficiently is by identifying any

anomalies in any part of a film at a glance. The slow system does not get

evoked unless the fast system signals it needs to be activated. To do that

effectively, the fast system has to be able to cope with all kind of films,

with technical factors, including artefacts, and with a full range of normal

variations. The immediate correlates are anatomical; the inferences are

pathophysiological.

Plainly,

radiologists are marvelous, especially at radiology. Every specialist has gone

through a similar kind of education in their own fields, but because so much of

fast system training is not conscious,

you cannot relate to alternate ways of instant processing in other

disciplines, even if they all share scientific foundations. You may know the end result of someone’s

clinical work, but not the way he or she got there.

There has been a

progressive ultrasound procedure drain from radiology into other fields that

have not had the years it takes for fast

system retraining for medical visual information work. It can succeed, but

usually for specific questions with simple yes and no kinds of answers. It

obviates the general diagnostic utility inherent in the method and the nature

of its form of tissue mapping. The fast

system response of an unfortunate number of radiology departments to turf

issues seems to have been to relegate ultrasound to the cabinet of curiosities

and to move on in other imaging directions.

Interpreting Outside

the Box

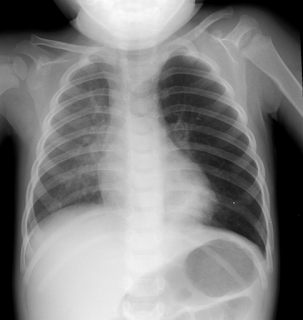

Articles about

ultrasound without images are like desserts without carbs. If you’re like me

you’ve already looked at the image. See anything interesting?

I selected an image

from a recent visit to a level III NICU. Among ultrasound’s advantages is that

high resolution, high contrast imaging can be performed in the isolette without

disturbing the endlessly fragile and vulnerable small premie. Studies tend to

be on demand when there is a suspicion of a problem. There are often no

baseline views for comparison or pre-emptive screening for early diagnosis.

The renal image was

from a female premie identified as a “normal” control, without any other

information provided. For the time being, go with this one view and assume

there were similar appearances for a few other papillae on both sides, but

nothing else. The fast system says:

yellow alert, something unusual and unexpected, presumptively pathological.

There is also a vibe that the problem is local and that its cause may have been

a drug side effect. The slow system cannot

go much further without a lot more information, starting with why this child

was delivered early and whether there may have been hydramnios. Then, it

will want ALL of the available clinical information, and it may want to review

what is known about renal pathology in newborns. Are the image findings

predictive of nephrocalcinosis or

predispose to papillary necrosis? Or will the appearance revert to normal with

the accelerated healing of fetuses and newborns? There is not any available

data to know the significance of the finding for renal development in early childhood

treatement or function in adolescence and adulthood. There is a nice review of high resolution

ultrasound of the pyramids which raises the same concerns by A Daneman et al,

Renal Pyramids: Focused Sonosgraphy of Normal and Pathyologic Processes in

Radiographics.

Prospect Theory

One of the main

research areas of Thinking has to do with how people make investments. What

struck me was the framing of the concept with a strong condition of “loss aversion.”

The first aphorism of Hippocrates states something like: Whatever you do, don’t

make things worse. Radiology has the operative dicta: Do not miss anything in

an image. Do not fail to provide information to contribute to a therapeutic

action plan. We are all really risk and loss aversive.

Kahneman and Tversky

found people faced with the same test problems may act to gamble one time and

not to another, depending on the way the problem is phrased, as well as their

moods and biases at the time. In addition, investors decided to “go for it” or “back off,” depending on

assessments of luck and expectation of rewards. This is the fast system at work

– biased, not quantitative. In our routine work, the equivalent might be the

way an exam is conducted for a happy situation like a normal pregnancy with a

goal of wellness confirmation versus the bleak scenario of staging an invasive

carcinoma or searching for metastases. Very busy work schedules, limited

patient contact time, and overly focused exam goals, promote reliance on

habitual fast thinking.

Comments

Post a Comment